An ageless Diva of a certain age

From the New York Times:

From the New York Times:Cher needs foot surgery. Something to do with a twice-broken toe. She was vague about this but said that earlier in the day, when she had gone shoe shopping, she couldn’t try on anything stylish or theatrical — anything Cher. Maybe next year, she said, after the operation.

Some friends wanted her to join them for a movie premiere in a few hours, but she was resisting. On this nippy evening in early November, as she curled up with a cup of cocoa in a Manhattan hotel suite, she was exhausted, even though she had just squeezed in a 45-minute nap, the heavy-lidded, woozy-voiced effects of which she was still shaking off.

Getting old, she said, stinks. She alternately stares it in the face and rejects it, teases that she’s 100 and puts the real number, 64, so far out of mind that, she said, “I should probably tattoo it on my hand to remember.”

Even without ink, her flesh — and joints and muscles — remind her. “It’s harder to do things,” she said. “I’ve beat my body up so badly, it’s amazing it’s still talking to me and listening to what I say. But I’ve got aches and pains everywhere.”

Coming from anyone else her age, this plaint would be unremarkable. From Cher it’s unthinkable — and deeply unsettling. Sure, we’ve lived with more Chers than there are Barbies, or even Madonnas: Sonny’s Cher; Silkwood Cher; Moonstruck Cher; disco Cher. But geriatric Cher?

Across nearly half a century of hit records, acclaimed movies, gaudy concert spectacles and a magnitude of celebrity for which the word fame is pathetically insufficient, Cher has come to seem the Sherman tank of divas, sometimes under fire but seldom in retreat, grinding ever onward, armored and unstoppable.

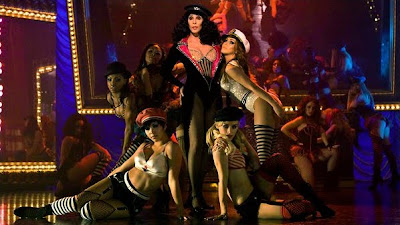

And in her new movie, Burlesque, a glossy musical that opens nationwide on Wednesday, she essentially promises that this won’t change. She plays a hard-boiled, die-hard showgirl (sound like anyone?) who takes a talented ingénue (Christina Aguilera, making her film debut) under lavishly feathered wing, and she has a set-piece power ballad, written expressly for her, in which her character pledges not to “fade out” and proclaims that she’s “far from over.” It’s titled “You Haven’t Seen the Last of Me,” and Cher belts it like it’s a battle cry — like her very life and ability to continue carrying off Bob Mackie gowns depended on it. For her most ardent fans multiplexes might want to stock smelling salts.

But the Cher sitting in a plush armchair in the Four Seasons Hotel in Midtown was a stiller, smaller, quieter creature.

She didn’t look old, not exactly. By all creaseless appearances, she and others have labored to prevent that.

She didn’t dress old, either. Her Jean Paul Gaultier T-shirt, textured and colored to resemble snake skin, clung to a svelte, taut frame, and when she rose from the chair at one point, her low-slung blue jeans dipped down far enough in the back to reveal a tattoo, fanning out broad and colorful below her waistline.

But her lulled, lulling manner better matched her fluffy brown socks, with a white pattern that was supposed to evoke ... snowflakes? “I don’t know,” she said. “I didn’t buy them. I’m just wearing them.” At a certain point and station, others take care of the tedium.

She hugged her knees to her chest and drained the cocoa, into which she had dumped a sprawling floe of whipped cream. A dab of it lingered on her lips long after the drink was done. Is that something you tell Cher? Mercifully, it disappeared before a decision had to be made.

Burlesque is her first movie in seven years, and she has only one other in the can, The Zookeeper, in which, she said, she supplies the voice of a lioness. During much of this celluloid slowdown Cher focused on her music — her four-year farewell tour, then a three-year commitment at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas — and she said that she has always considered movies an extra, bonus career. Hollywood insiders add that she has become harder to cast, given the odd fit of her age and stubbornly ageless visage.

Her Vegas show winds down in February. A tour will most likely follow, but Cher seemed more enthusiastic about a humbler project on the horizon. Sometime early next year she said, she will begin playing host to a pajama party of sorts on the Turner Classic Movies channel, introducing and reflecting on old favorites of her choosing, which will be shown after midnight. And thus will Cher don yet another new persona — as a cocoalike balm for cinephile insomniacs.

It’s surprising, yes, but also sensible, and a window into a central secret of Cher’s success. For all her audacity (the envelope-pushing outfits, the tabloid-chum affairs) she has always been acutely conscious of limits — at least her own.

Although her span of hit singles stretches all the way from “I Got You Babe” in 1965 through “Song for the Lonely” in 2002, Cher has never taken that astonishing durability as license to explore any genre (Broadway musicals say, or jazz standards) that tickled her fancy.

She nabbed top acting honors at the Cannes Film Festival for her role as the red-haired biker mom in Mask in 1985 and won the best actress Oscar for playing a (briefly) gray-haired widow in “Moonstruck” two years later, but she never got it in her head to scale Shakespeare.

“Look, I have a very narrow range,” she said. “I’ve never tried anything more than playing who I am. If you look at my characters, they’re all me.”

Although she expresses a pointed political opinion from time to time, it’s never part of a sustained campaign, and it’s never grandiloquent, the way some Hollywood peers can be.

Mike Nichols, who directed her in Silkwood, for which she received an Oscar nomination as best supporting actress, said: “I heard her on the radio once, somebody was interviewing her, and they said, ‘How do you feel about the Middle East?’ She said: ‘Listen, I’m Cher. You don’t want to know what I think about the Middle East.’ She knows who she is.”

There’s something gloriously matter-of-fact about her, and during a conversation of more than 90 minutes there wasn’t a single topic that made her flinch.

The transformation of her daughter, Chastity Bono, into a son, Chaz? It has been difficult to watch, she said, but not entirely unexpected. “We talked about it a lot over the years,” she said. But she had always attributed her daughter’s occasionally stated discomfort with her gender to a general sadness brought on by drug abuse.

The love of her life? The answer wasn’t Sonny Bono, but the onetime bagel baker Robert Camilletti, “even though he’s like 1,000 years younger.” She was 40 and he was 22 when they met in the late 1980s, and he steadfastly took care of her, she said, during a furiously busy period when three movies (“The Witches of Eastwick” and “Suspect” in addition to Moonstruck) and an album came out in a span of just two years.

There’s no man now, although she recently dated — and remains friendly with — Ron Zimmerman, a comedian she met on Facebook, of all places. She has a personal page, noticed funny wall postings of his on a friend’s page, and began messaging him.

She is on Twitter too and has used it not only to announce Burlesque news but also to report on grocery shopping during a trip to Maui (“Spent 10 min at Safeway there trying to buy healthiest Butter!”) and dole out random beauty tips.

“I’ve been around 100 yrs I know a Gazzilion cool things! I’m pass’n it on xxme,” she wrote in a Twitter message with typically erratic spelling, spacing and punctuation. Shortly after that she began to evangelize about exfoliation, proclaiming that “every woman should scrub!” and then clarifying, in a follow-up message, “&&& don’t

scrub Hard.”

It’s an odd existence, Cher’s. When she recounted a late-night gabfest with two girlfriends in the bedroom of her Malibu manse not long ago, the gabbers in question were Joan Rivers and Kathy Griffin. When she flashed back to a favorite exercise class in Beverly Hills decades ago, the fellow crunchers and squatters were Raquel Welch, Ali MacGraw and, to a more limited and grudging extent, Barbra Streisand, who “would go over, do two little things, and then walk around and talk,” Cher said.

She refers to most of these people by first name or nickname only, figuring you can fill in the blanks. Nicky is Nicolas Cage, Kurty is Kurt Russell, Mich is Michelle Pfeiffer and Nony is Winona Ryder, who starred with Cher in “Mermaids” in 1990 but suffered a career setback after a subsequent arrest for shoplifting.

“It’s such a drag that some crimes are cool and some crimes are uncool,” Cher said. “I mean, it would have been better if she was a heroin addict, went away to rehab. People are ready for that. They understand that.”

She said she tries to steer clear of uncool. She is cautious. Even after David Geffen, her most trusted adviser, told her she had to do Burlesque, she said no, she said maybe, she asked for rewrites and then brought in the playwright John Patrick Shanley, who wrote Moonstruck, for additional rewrites after shooting had begun. She was even granted permission to weigh in on takes of her scenes.

“Look, I was nervous,” she said. “And I hadn’t made a movie in a long time. And I have my own opinions about things.”

Stanley Tucci, who plays her caustic sidekick in the movie, said that before many scenes were shot, she would go through the same doubt-ridden ritual, telling him: “I don’t know how to act. I don’t know my line. I can’t do this. Stanley, help me.”

But she would be fine, he said. Better than fine.

In fact the Burlesque set became known around Hollywood not for any insecurities Cher nursed or demands she made but for bitter, loud fights between Clint Culpepper, the president of Sony Pictures’ Screen Gems unit, which produced the movie, and Steven Antin, the movie’s director and writer. The two were longtime romantic partners when shooting began.

Cher said that Mr. Culpepper indeed did a fair deal of yelling. “If I was Steven, I might have punched him,” she said. But, she added, that’s just how Mr. Culpepper is: passionate. “It didn’t bother anyone.”

“When you’re making a movie at this pace, sometimes things get heated,” explained Mr. Antin, who said that he and Mr. Culpepper have “always had a relationship of high drama, so for us it wasn’t any different.” He declined to answer whether he and Mr. Culpepper were still a couple. Cher said she didn’t know and couldn’t tell.

In this movie, as in others, she doesn’t overreach. She cedes the spotlight to Ms. Aguilera, who has at least double her screen time, and Cher performs just two big production numbers, during which she doesn’t so much dance as sidle, strut, pose. They’re a contrast to the rest of the choreography, which has Ms. Aguilera and others in the cast bending, bouncing and whirling like a team of Eastern European gymnasts on a Four Loko tear.

“The girls in that film — the oldest one was 30,” Cher said. “Christina’s 29.”

“You’re around these girls who are 20 years old with perfect bodies, and you remember when you used to have a perfect body,” she added. She shook her head. Smiled. “Just to stay in the competition,” she added, but stopped there, leaving the sentence unfinished.

A few feet away was a treadmill, installed in the suite for her use, and between trudging out, trouperlike, to “Live With Regis and Kelly” and “Late Show With David Letterman” and the rest of it, she was putting in her time on it.

Staying thin, she said, used to be relatively effortless. Not anymore. But people have certain expectations of her.

And she has certain expectations of herself, including this one, a sort of pledge she made just before saying goodbye.

Not too long from now, Cher predicted, “I’ll be back wearing high heels again.”

Comments